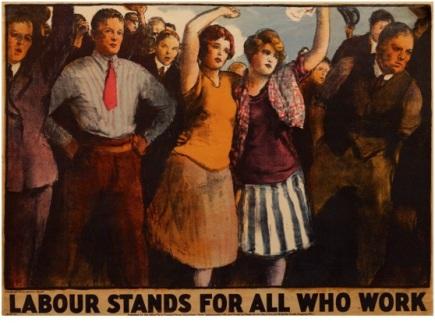

On Thursday 14th June, academics and advertising professionals gathered at the People’s History Museum in Manchester to discuss the past, present and future of political communication. The conference, sponsored by the Centre for British Politics, also marked the end of the exhibition Picturing Politics: Exploring the British Political Poster curated by PhD candidate Chris Burgess, who also organised the conference.

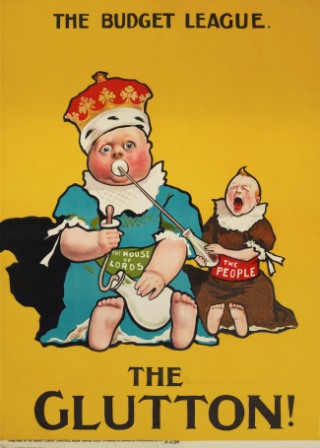

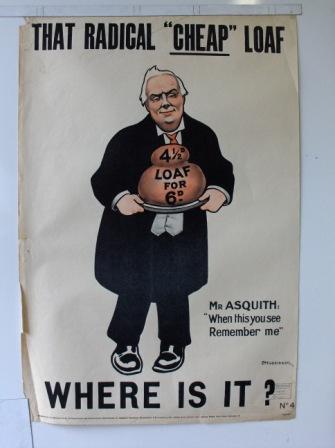

Most contributors focussed on the communication between political parties and the people, specifically how the former have tried to influence the later. What was immediately apparent is just how varied such communication can be. David Thackeray explored the communication between local candidates and electors in the form of election addresses. This set the mark for many of the papers as a strong theme emerged of the importance of communication previously ignored by historians. Nick Mansfield’s paper on political banners demonstrated that during the twentieth century these often-beautiful objects had a role in extra parliamentary democracy, single-issue pressure groups, and even intra-party communication. Mansfield’s findings demonstrate that there is much more to banners than the expression of nineteenth century masculine trade unionism. Jon Lawrence showed that even in those halcyon days before spin-doctors, politicians used their dress to speak to the people. An image of James Ramsay-MacDonald wearing a lounge suit and smoking a cigarette demonstrated the Labour leader’s modernity. Questions after Lawrence’s talk naturally led to discussion of that most iconic/infamous political garb, Michael Foot’s donkey jacket (which wasn’t a donkey jacket), which provoked many delegates to look at the guilty object during lunch as it is on display in the Museum. James Thompson also spoke of the visual, vividly describing the spectacle of Edwardian London County Council elections. Thompson argued that campaigning in the Edwardian period was as much about sight as about sound. He vividly spoke of a parade of floats used to persuade people to vote including a man standing on a ship with the accompanying slogan ‘one man one boat’, certainly the pun of the day.

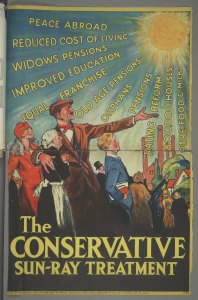

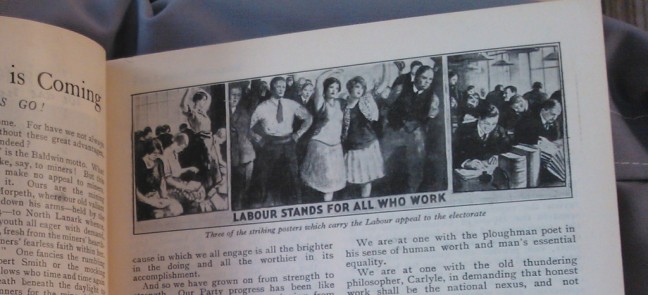

Posters often literally loomed large in many papers. Stuart Ball referred to posters in his analysis of Conservative communication in the inter-war years. Former Saatchi employee and current researcher Graham Deakin examined the well-known poster Labour Isn’t Working and how it helped establish the 48 sheet bill board in elections after 1979. Rachel Grainger also focussed on Labour Isn’t Working, applying semiotic method to unpick the posters meaning. Chris Burgess also spoke in detail about Labour’s poster Yesterday’s Men and how it contributed to the formation of political communication during and after the 1970 election.

One of the key points that emerged from the discussion was the role of ‘professional’ or commercial advertising in political communication. Both Jon Lawrence and Stuart Ball highlighted media management as key to communication in the inter-war period. This was a theme picked up by Dominic Wring on his paper on Herbert Morrison, Labour and the 1937 London election, describing that as Labour’s first ‘professional campaign’. Jim Aulich found modern techniques outside the party structure. He demonstrated the sophistication of left-wing material designed to promote Soviet Russia to the British people during the Second World War. In the final paper of the day Simon Cross explored the changing nature of the party election broadcast. Cross’ paper provided a neat ending in that it argued that while much has changed with PEBs over the course of the second half of the 20th century strong continuities were evident. Indeed, a line emerged throughout the conference that while parties and communication experts often claimed to be innovating new techniques, in reality there was much reinvention.

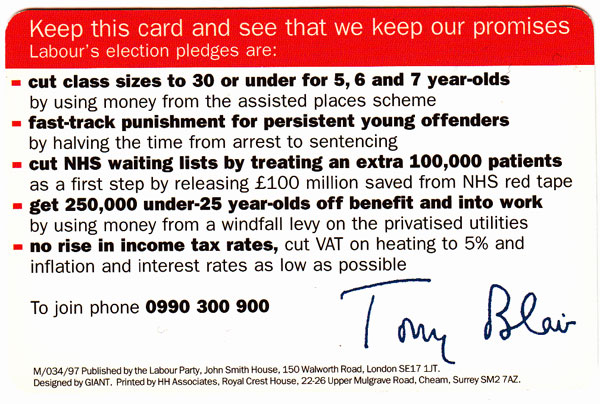

The day ended with a round-table discussion. The panel included advertising executive and blogger Benedict Pringle (www.politicaladvertising.co.uk), ad-excutive and former head of the Lib Dem online campaign in the 2001 and 2005 elections Mark Pack (www.markpack.org.uk) Jon Lawrence, Stuart Ball, and academic and co-author of the latest Nuffield election study Philip Cowley. Professionalisation, in the form of the influence of US advisors, was a topic that concerned the panel. There was a general puzzlement as why British parties relied so heavily on such figures, given the radical difference between UK and American electoral conditions. Naturally, the future of campaigning came up and Mark Pack made the point that now the most widely read adverts were text messages. Phil Cowley also emphasised the contemporary importance of direct mail to political parties – and how little interest there was in studying this form of communication amongst journalists and academics alike. Those looking to research some new evidence for their PhD, take note.

The conference ended with a lively but inconclusive discussion on the political merits of Banksy’s work, provoked by a question from the floor.